Alright, so someone asked me about the 72-hour mental health hold thing here in Oregon, and man, let me tell ya, I got a front-row seat to that whole process a while back. It’s not something you really get until you see it unfold. I figured I’d share what I went through and what I saw, just my own experience, you know?

How It All Kicked Off

It started with a friend. We’ll call him Dave. Dave was spiraling, and it got scary. Not just “having a bad week” scary, but like, “we’re genuinely worried for his life” scary. We tried talking to him, tried to get him to see a doctor, the whole nine yards. But he was just too far gone in that moment, not thinking straight at all. We spent a couple of days, felt like weeks, just trying to keep an eye on him, hoping he’d snap out of it. He didn’t.

Eventually, things got to a point where we had to make a choice. Do we keep trying on our own and risk something terrible, or do we call in people who are supposed to know how to handle this? It was a gut-wrenching decision, believe me. But we made the call. We ended up calling the county crisis line, explained the situation, how he was talking, what he was threatening to do. They were calm, asked a lot of questions. Real specific stuff.

The Professionals Step In

Next thing, a couple of folks showed up. Not cops in a blaring siren car, which was a relief, but mental health professionals, part of a crisis team. They came into the house, talked to Dave, talked to us. They were very direct but not unkind, you know? They had to figure out if he met the criteria: basically, was he a danger to himself, a danger to others, or unable to take care of his basic needs because of a mental health issue. In Dave’s case, it was clearly danger to himself.

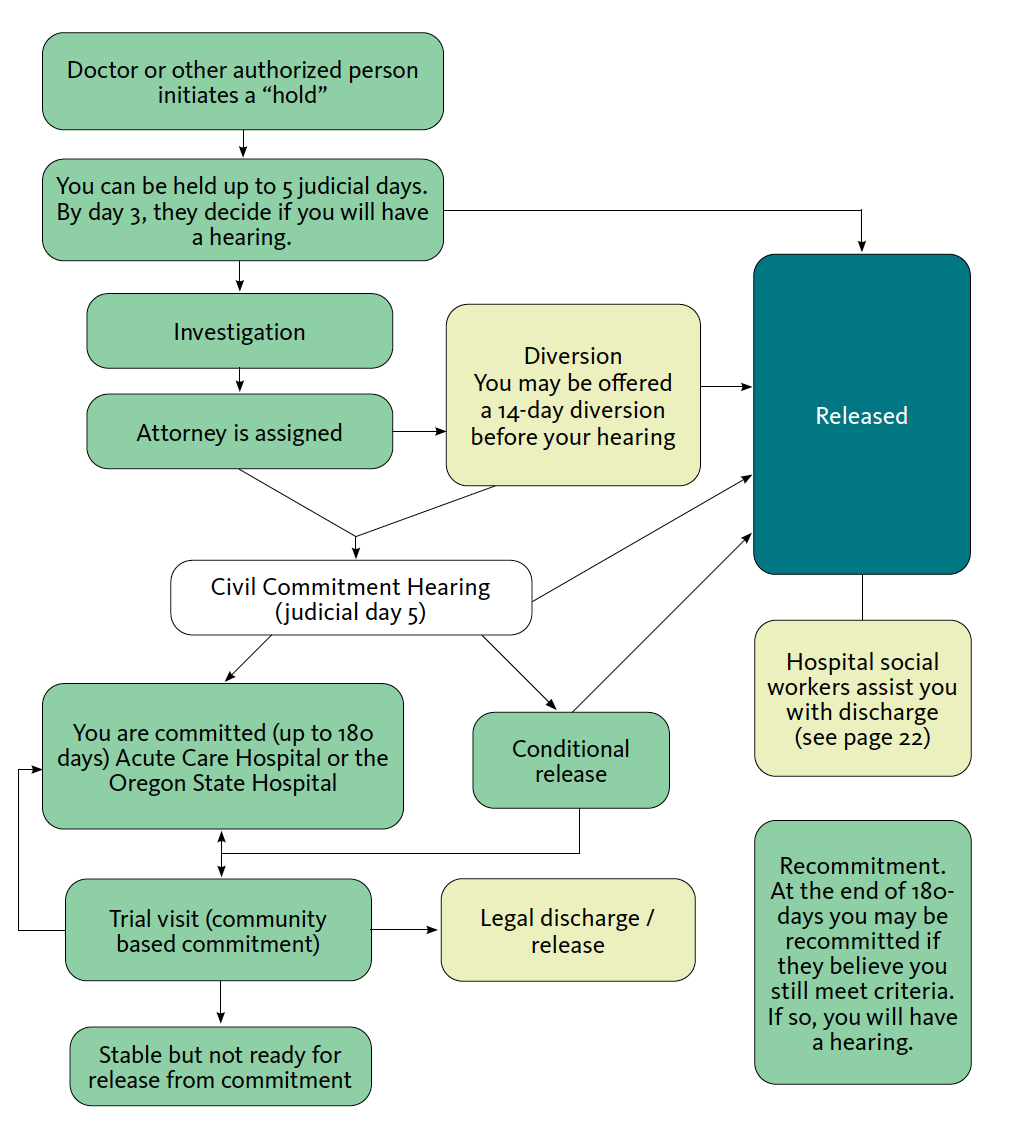

After about an hour of talking and observing, they made the call. They said he needed to be on a hold. They explained it wasn’t a punishment, but a way to keep him safe and get him evaluated. That’s when they use the term “Director’s Hold” or “Peace Officer Hold,” depending on who officially kicks it off. For Dave, it was the mental health professionals who initiated it, working with the authorities.

Then came the transport. That part was tough to watch. He wasn’t fighting, just sort of numb. They took him to a designated hospital, one that had a psychiatric unit. We couldn’t go with him in the transport, obviously.

The 72 Hours (Which Isn’t Always 72 Hours Sharp)

So, this “72-hour hold” thing, it’s a bit misleading. It’s not like a timer starts and at 72 hours, boom, you’re out. It’s more like up to 72 hours, and often it’s business days, for them to evaluate and decide what’s next. Weekends and holidays can stretch things out. We found that out pretty quick.

During that time, from what I gathered and what Dave told me later:

- Observation: Lots of it. Nurses and staff checking in regularly.

- Medication: They assessed if he needed meds to stabilize him. He did, and they started him on something.

- Seeing a psychiatrist: He met with a psychiatrist who did a proper evaluation. This wasn’t like a deep therapy session right away, more like crisis stabilization and assessment.

- Basic Needs: Making sure he ate, slept (as much as possible in a strange place), and was physically safe.

Getting information was tough. We’d call, and because of privacy laws (which I get, but it’s frustrating when you’re worried sick), they couldn’t tell us much. Dave had to give permission for them to talk to us. It was a lot of waiting by the phone.

What Happened After

For Dave, after about two and a half days, the psychiatrist decided he was stable enough to be discharged. But it wasn’t just “okay, you can go home now.” They worked out a safety plan with him. This meant follow-up appointments, medication management, and us, his friends, being part of his support system. They wouldn’t have let him go if they thought he was still an immediate risk.

Some people might need longer, or they might transition to voluntary treatment, or, in some cases, if they’re still a risk and won’t stay voluntarily, there are longer-term commitment processes. But Dave’s was the 72-hour evaluation hold that ended with a discharge and a plan.

My Takeaway from All This

It’s serious business. This isn’t something that happens lightly. There are actual legal criteria that have to be met. It’s a last resort when someone is in acute crisis.

It’s not a magic fix. The hold is about immediate safety and evaluation, not curing deep-seated issues in three days. It’s the start of a longer journey, usually.

The people involved, mostly, are trying their best. The crisis team, the hospital staff – they deal with tough stuff every day. It’s a hard job.

It’s emotionally draining for everyone. For the person on the hold, for their family, for their friends. It’s a tough road.

So yeah, that was my dive into the 72-hour mental health hold in Oregon. It’s a system designed to protect people at their most vulnerable, and while it’s not perfect, and it was scary to go through, I’m glad it was there when Dave needed it. Just sharing my bit, hoping it sheds some light on how it actually works on the ground.