Okay, let me walk you through something I saw happen a while back. It involves a local political race and this whole business of commissioning a poll.

Getting Started with the Idea

So, a friend of mine, let’s call him Jim, decided he was gonna run for a town council seat. Full of energy, you know? Knocking on doors, making calls. But after a few weeks, we were all kinda guessing about how things were really going. You hear good things, you hear bad things, but it’s mostly just noise. Someone on his small team, I think it was his sister-in-law, said, “We need a poll! We need to know where we actually stand.”

Jim wasn’t immediately sold. The first thing he asked was, “How much does that cost?” Turns out, it’s not cheap, especially for a small local campaign mostly running on fumes and volunteer hours. We spent a good evening just looking up different polling companies, trying to figure out what was even possible.

Digging into the Details

Once Jim sort of accepted that a poll might be necessary, the real work started. This wasn’t just like ordering pizza. We had to:

- Figure out the Goal: What did we really need to know? Just name recognition? What issues mattered most to people? Where was his opponent strong or weak?

- Find a Vendor: We contacted maybe three or four different polling outfits. Some were big national names (way too expensive), others were smaller, more local or regional groups. Getting quotes and understanding what they offered took time. They all had different ways of doing things – phone calls, online panels, etc.

- Craft the Questions: This was probably the hardest part. Everyone had an opinion. Jim wanted to ask about his pet project idea. His campaign manager wanted to test messages against the opponent. I remember suggesting we keep it simple. The polling company also had their own standard questions they recommended. It was a lot of back-and-forth just to finalize the questionnaire. We spent hours debating wording. Seriously, hours.

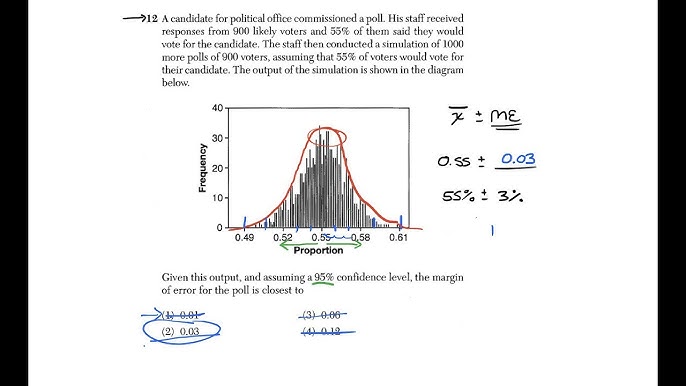

- Define the Audience: Who should they even call? Registered voters? Likely voters? People in a specific neighborhood? The pollsters guided this mostly, talking about sample size and margin of error. Sounded complicated, but basically, they needed enough random people to make the results somewhat meaningful.

Pulling the Trigger and Waiting

After weeks of discussion and penny-pinching, Jim finally signed the contract with one of the regional pollsters. It felt like a big step. Handing over that check was painful, I could see it on his face. He kept saying, “This better be worth it.”

Then came the waiting game. The polling company went off and did their thing. It took about ten days, I think. In the meantime, the campaign just kept doing what it was doing, but everyone was kind of holding their breath, waiting for the numbers.

Seeing the Results (and the Reality)

When the results finally came back, it wasn’t some magic answer. It was just data. Some of it confirmed what we suspected – people cared about taxes, shocker. Some of it was surprising – an issue Jim thought was a winner barely registered. His name recognition was lower than he hoped.

The key thing I observed wasn’t just the numbers themselves, but how the campaign used them. They didn’t radically change everything overnight. Instead, they tweaked the message. They focused more on introducing Jim to voters since recognition was low. They started talking more about the issues the poll showed people actually cared about, not just the ones Jim was passionate about initially.

It was a practical tool, but not a crystal ball. Seeing the process up close, the arguments about questions, the cost anxiety, the careful interpretation of results – it showed me that commissioning a poll is a real grind, a calculated risk, especially for smaller campaigns. It’s less about getting a perfect prediction and more about getting a slightly clearer snapshot to guide the next steps. Definitely learned a lot just watching it unfold.